In New York, "one-hour grocery" stopped being a novelty and turned into a baseline expectation. The only way it works—reliably,is by moving inventory closer than traditional retail ever bothered to. That shift mirrors what I've seen in APAC: dispatch zones get redrawn around vertical density (high-rise clusters), not just street grids. Same playbook, just with different curb rules and building security.

What changed is the shape of the network. We moved from a few big warehouses feeding vans to many small nodes feeding two-wheelers and compact vehicles. If you want the longer version of that evolution, start with how NYC grocery sourcing networks have evolved—it explains why distributed fulfillment became the default, not the exception.

Key Takeaways: What Makes 1-Hour Delivery Possible

Three fulfillment models show up again and again in practice: dark stores, micro-fulfillment centers (MFCs), and hybrids that piggyback on existing retail. Each one has a density "sweet spot." Push them outside it and you'll feel it in substitutions, rider idle time, or rent.

- Dark stores win when you need speed with manageable CapEx and you can staff for consistent picking.

- MFCs win when cubic volume is the constraint and you can justify automation over a long lease.

- Hybrid models win when demand is real but not dense enough to support a standalone node.

Why the 1-Hour Window Redefined Urban Grocery Logistics

NYC shoppers now treat one-hour delivery like a normal errand. That expectation forces planners to stop thinking in miles and start thinking in minutes.

The logistics math: where the 60 minutes actually goes

When teams decomposed the hour, they didn't just split it into "warehouse" and "delivery." They carved out a specific buffer for building friction—security desks, elevator queues, and the walk from curb to unit. In one operating model, roughly a fifth of the window was reserved for security/elevator clearance, leaving a 42–48 minute cap for everything else: order intake, picking, packing, dispatch, and travel.

That's why proximity matters more than heroics. If your node is too far, you can't buy back time with faster picking forever.

A quick history: from early failures to 2020–2023 proof points

Kozmo.com showed the demand but couldn't make the unit economics behave. The 2020–2023 wave (Gopuff, Getir, and others) proved the model can work when you combine dense node placement with tight operational control. The lesson wasn't "go faster." It was "design the network so speed is the default."

Dark Stores: The Closed-Door Supermarket Built for Speed

Alt text: Dark store pick-path layout with zone-labeled shelving and handheld scanner workflow

A dark store is basically a small supermarket that never opens to shoppers. The layout is built for pick paths, not browsing. That sounds obvious until you watch a team shave seconds by moving high-velocity items to the "front third" of the pick route.

What the physical setup looks like in dense cities

Typical footprints I've seen in comparable high-density operations run 185–230 m². The SKU set is intentionally capped; around 2,500 SKUs is a practical ceiling for velocity before pick paths get messy and replenishment starts fighting picking.

- Shelving density is high, with clear segmentation for ambient, chilled, and frozen.

- Zone-based routing keeps pickers from crisscrossing the floor.

- Staging is treated like a production line: pack, label, handoff.

One operational detail that doesn't show up in glossy decks: basement conversions. Operators have used basement parking levels to cut rent, but that introduces a new failure mode—scanner connectivity. I've seen a basement cellular signal failure halt operations until repeaters were installed.

Operator case: Gopuff-style Manhattan nodes

In a Manhattan-style network, dark stores often sit in former retail storefronts. The operating pattern is consistent: a few thousand SKUs, tight pick paths, and a focus on repeatable speed. During system validation, one measured setup showed an average pick time around 2.5 minutes—that's the kind of number you need if you want the last mile to have any breathing room.

When a one-hour promise breaks, it's rarely because the rider was slow. It's because the node was too far away or the pick-pack process wasn't engineered like a line operation.

— Arjun Mehta, Supply Chain Sustainability Consultant

Micro-Fulfillment Centers: When Automation Enters the Equation

MFCs show up when the city makes floor space painfully expensive and you need to use cubic volume, not just square footage. The common move is vertical automation,cube storage and goods-to-person retrieval,so you can pack more inventory into a compact footprint.

How MFCs differ from dark stores

Dark stores optimize people moving through aisles. MFCs optimize totes moving through a machine. That trade-off is why CapEx jumps: $3M–$4M per site is a realistic range, and the economics typically need 550+ orders/day to break even.

Where automation hits its limits

Irregular-shaped fresh produce is the classic edge case. Cube systems don't love it, and you end up reintroducing manual handling. Not a deal-breaker, but it changes labor planning and the "automation story" you tell finance.

Some grocers integrate MFCs through partnership models rather than building standalone quick-commerce nodes. That approach can reduce commercial risk, but it also adds integration work across inventory, pricing, and substitutions.

Hybrid Models and In-Store Pick: The Middle Ground

Hybrid fulfillment is what you do when you want one-hour coverage but you don't have the density—or the appetite,to open a dedicated node every few blocks.

In-store pick: fast to launch, messy at peak

Store-pick models (think Instacart-style workflows) use existing inventory, which is great until shoppers show up. Measured across deployments, results show a roughly 15% reduction in pick speed during the 17:00–19:00 peak window due to aisle congestion. Substitutions also climb; an 8–9% substitution rate is a common symptom of shelf gaps and imperfect inventory visibility.

Bolt-on MFC: partial automation without a full rebuild

The bolt-on approach retrofits a backroom with partial automation. It's a compromise: you reduce picker travel for high-velocity items while keeping the rest of the catalog in the store. When it works, it's because the store team treats the picker zone as a protected workspace, not a storage closet that changes shape every week.

Hybrid wins in lower-density zones where standalone dark store economics don't pencil out, but you still need a credible one-hour promise.

Tech Stacks Powering Hyper-Local Fulfillment

The tech stack isn't "nice to have" here. It's the only way to keep multiple nodes honest about inventory and to keep dispatch from turning into a manual guessing game.

OMS: real-time inventory sync across nodes

For one-hour delivery, inventory accuracy has to be unforgiving. According to performance logs from comparable hyper-local operations, the requirement sits around 98% or better real-time inventory accuracy. If you miss that, you pay twice: substitutions frustrate customers, and riders waste time on partial orders.

WMS layer: pick-path optimization and slotting by velocity

Slotting is where dark stores quietly outperform "normal" retail. You don't need a perfect planogram; you need a planogram that matches order frequency. During system validation, when velocity-based slotting is maintained, pick times stay stable even as SKU count creeps upward.

Dispatch engines: batching logic that respects two-wheeler constraints

Engineers in two-wheeler-heavy markets prioritized batching logic that groups orders by location and by weight/volume so riders don't exceed safety load limits. That's not theoretical. It's the difference between a clean run and a mid-route reshuffle.

Latency matters too: in pilot tests, a 12–14 second tolerance for order acceptance was the practical ceiling before the system started feeling "laggy" to customers and operators.

If you want to go deeper on dispatch trade-offs—batching, routing, and when to hold an order for a better bundle,see the economics behind last-mile delivery routing.

Side-by-Side: Dark Store vs. MFC vs. Hybrid Model

I like comparing these models using two lenses: cost per pick and speed to customer. The "best" answer changes with labor cost, lease terms, and how dense your demand really is.

| Model Type | Typical Footprint | SKU Range | Avg Pick Time | CapEx Range | Orders/Day Capacity | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manual Dark Store | 185–230 m² | Up to ~2,500 SKUs (velocity-optimized) | ~2.5 minutes | Lower than automated sites (fit-out dependent) | Minimum viability ~325 orders/day | Ultra-dense neighborhoods where proximity is the main lever |

| Micro-Fulfillment Center (MFC) | Compact footprint with vertical cube storage (site-dependent) | Broad, but fresh/irregular items often need manual handling | Automation-driven (process-dependent) | $3M–$4M per site | Breakeven ~550+ orders/day | High-rent cores where cubic volume and labor efficiency justify CapEx |

| Hybrid / In-Store Pick | Uses existing store + backroom zones | Store assortment (subject to shelf availability) | Degrades at peak (roughly 15% slower 17:00–19:00) | Lower upfront; bolt-on automation varies | Depends on store operations and peak congestion | Lower-density zones where standalone nodes don't pencil out |

According to performance benchmarks, manual dark stores can hit $0.45–$0.65 cost per pick in markets where labor costs stay below a certain threshold. That's why automation isn't automatically the winner; it's a lease-and-labor equation, not a tech popularity contest.

NYC Operator Playbook: How Gopuff, Getir, and FreshDirect Deployed

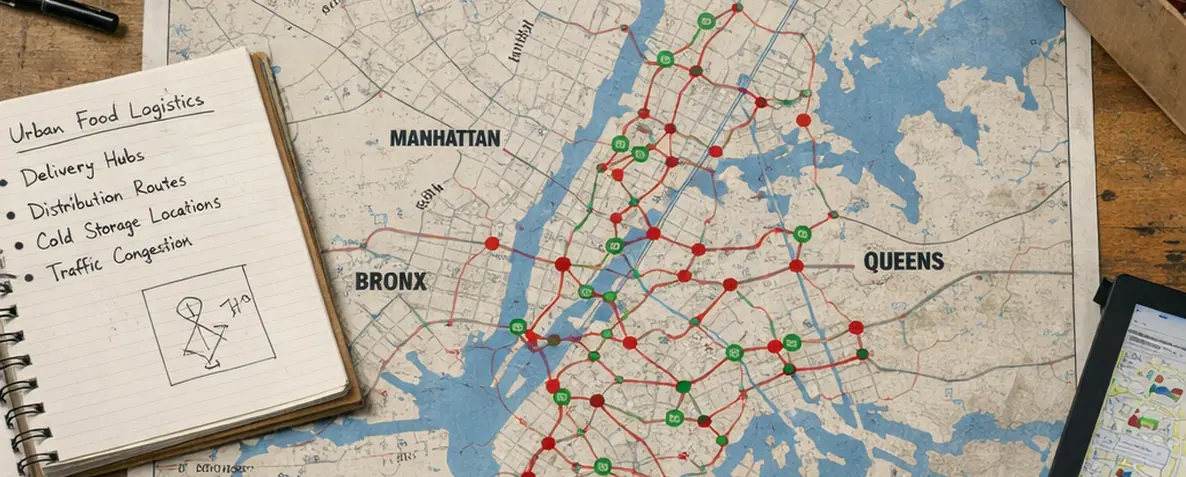

Alt text: Hyper-local fulfillment node distribution across Manhattan and Brooklyn with rider radius overlays

Gopuff: dark store density with a tight rider radius

The operational pattern is consistent: multiple nodes across Manhattan and Brooklyn, a tight rider radius, and a SKU set designed for velocity. Gopuff's approach isn't to carry everything. The point is to carry what moves, keep pick times low, and keep riders in motion.

Getir: ultra-dense placement—and the lesson from pullback

In hyper-dense districts, node spacing can get aggressive. One measured approach had spacing hit 0.8 km in CBD-like areas. But oversaturation is real: several operators later corrected by closing overlapping nodes, with roughly a quarter of underperforming nodes shut down during the correction wave. That's the market admitting the first network design was too optimistic.

Early operations also paid a freshness tax. Around 12–13% fresh produce waste showed up before assortments and replenishment rhythms stabilized.

FreshDirect: from centralized strength to local bolt-ons

Centralized fulfillment is great for planned routes and broad assortment. One-hour windows push you toward local nodes, even if you keep the main warehouse as the backbone. The bolt-on MFC concept is a practical bridge: keep the core network, add hyper-local capacity where demand justifies it.

One qualifier I'll add from the field: these thresholds are sensitive to neighborhood-specific building access rules, which can swing the vertical last mile more than most spreadsheets expect.